If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants

If I have seen further than others, it is because I am surrounded by dwarfs.

The dwarf sees farther than the giant, when he has the giant’s shoulder to mount on.

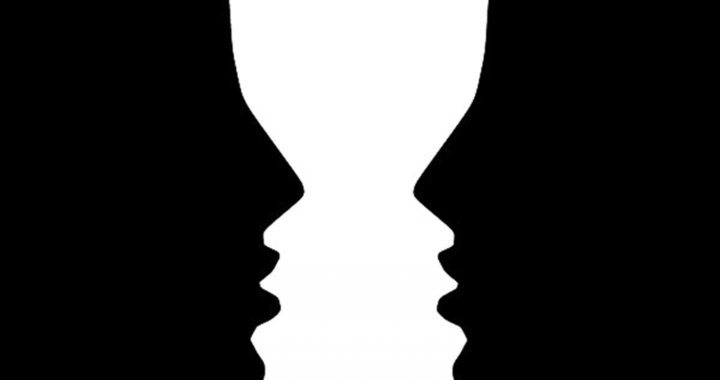

There is a historical revisionism movement in academia today to minimize the impact of the individual rogue, to deny any possibility of poesis, and to replace it with a transcendental consensus-driven knowledge production process into which the personality must be subordinated. “If you hadn’t discovered it, someone else would have,” they say. It is claimed that the polymath died out in the 19th century due to the vast expansion of human knowledge, and modern educational theory says that gifted children are to be guided towards ’eminence’ in an ever-expanding collection of increasingly obscure academic specialties.

This article is about public people who influenced me. I don’t know if they would all like seeing their names together on a list, but it is through no fault of their own.

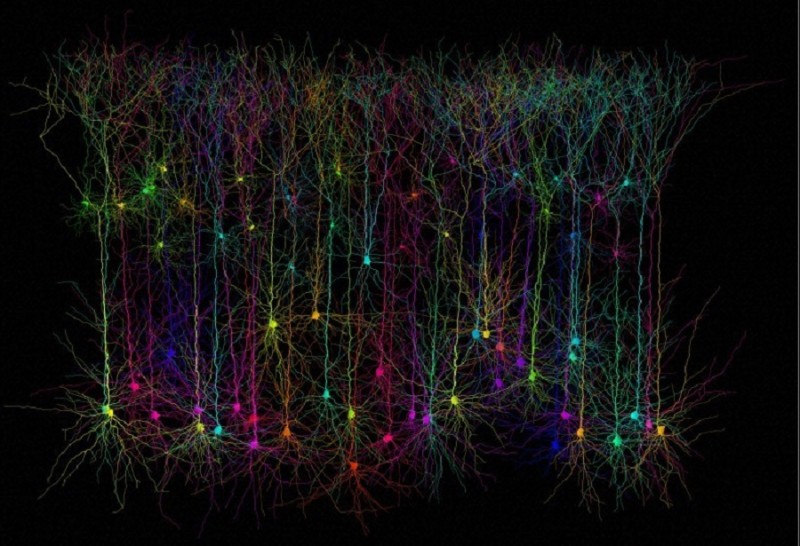

I separately review the history of brain mapping, and my debts to the great body of neuroscience here.

I am indebted to Carl Jung for the inspiration of using archetypal patterns to explore the mind, and generating the interest in archetypal psychology that in turn drew my own interest in such people’s interest (hopefully that made sense). Jung is of course situated at a nexus of a long history of esoteric, Eastern, and Western traditions, and followers such as James Hillman and Joseph Campbell. Despite being quite self-conscious that people would think he was a loon, Jung boldly “let himself go” in plunging into the deep waters of the psyche, the esoteric, and the Collective Unconscious. I took my own plunge over the past few years, tethered to a rock for safety, and I am grateful to Jung for showing the way. I am fortunate to have resources at my disposal that Jung did not have: the world’s research at my fingertips, informatics knowledge, and a hundred years of neuroscience work to draw inspiration to complement the mystical literature.

Olaf Stapledon is an undeservedly obscure British writer from the first half of the 20th century. He was the one who first imagined much of the later science fiction genre: planetary terraforming, genetic engineering, collective hive minds, and Dyson spheres that . His works stand out as mythology set at a universal level, and he spends much of his efforts at expressing his allegience to something he called the “spirit” of man. Stapledon’s spirit is related to Hegel’s geist but elaborated in his own aesthetic way.

Olaf Stapledon used a metaphor of the jackdaw to describe himself. A jackdaw steals shiny bits of treasure from across the landscape and fashions it into a nest that meets his own aesthetic preferences. His philosophy drew eclectically from Western and Eastern sources. I have adopted Stapledon’s jackdaw as my own avatar.

Stapledon was a man of superior intellect and erudition. His works are semi-autobiographical but he was quite self-conscious about sounding conceited and pretentious. Odd John was a book about a super-intelligent mutant and how he grew up; Stapledon’s narrator was a journalist who befriended the boy. Last and First Men was written from the standpoint of an Englishman whose mind was in direct telepathic contact with a man millions of years in the future, who in turn narrated future historical events. Star Maker was similarly written as an everyman, but his testimony was through the experience of joining a Cosmic Mind. My character Hermes Phimegistus is a hat-tip to this mode of authorship, and the sweep of Stapledon’s mythology inspires me to strive for the grandeur of his visions.

Stephen Wolfram

I think a lot about Stephen Wolfram, the founder of Mathematica. While working for Richard Feynman as a young wunderkind at CalTech, Feynman advised him to pursue his research without undue interference from others. So he started his own company, created a peerless tool for mathematical exploration, and studies in whatever way he feels like in whatever manner he wants. His magnum opus book, A New Kind of Science, is a work of wide-ranging erudition in search of deep principles with which to simplify complexity, and connect this to the universe at large. People who try to stretch boundaries like this earn the envious scorn of young grad students who try to knock them down. While I am nowhere near his caliber of genius, I am inspired by his attitude and accomplishment. Where others hear arrogance into his delivery, I hear child-like enthusiasm from a man in his 60s.

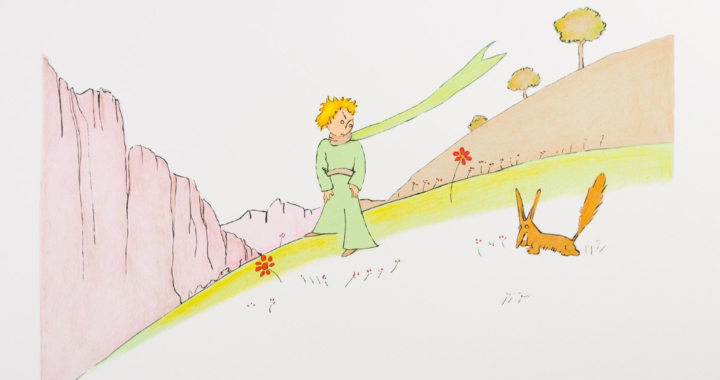

Antoine Saint-Exupery was a tragic puer aeternus who spent his life in search of ‘the why’. His classic The Little Prince is the beloved favorite book of many. The trip through allegorical little planets, each representing an archetypal personality that we all meet in life, directly inspires the Neuromythograph, with its connected caverns, each housing a single archetype. Whereas the Little Prince had eight planets, the fully-elaborated Neuromythograph has about 700 of approximately 1200 entities populated as of this writing. Indeed, neuromythography is a brain-inspired sequel to The Little Prince gone terribly awry!

Sextus Empiricus

Sextus Empiricus was a Roman physician from whom we have learned the most about a Greek philosopher called Pyrrho, the eponymous founder of Pyrrhonism. Pyrrho allegedly accompanied Alexander the Great during his conquest of India, where he encountered the gymnophilosophers (“naked philosophers”), who were early Hindu mystics. Pyrrho emphasized a form of skepticism that held that maintaining strong convictions about truths is the cause of suffering, and that one ought to try to be at peace with leaving issues undecided. Sextus Empiricus applied this to three school of medicine that were dominant in his time: the Rationalists (who relied upon top-down reason), the Empiricists (who relied upon bottom-up evidence collection) and the Methodists (who relied upon intuition in the moment). Confusingly, Sextus was a leader of the Empiricist school, but his writing takes a strongly Pyrrhonist and Methodist stance.

I find myself sympathetic to Sextus Empiricus’ skeptical Pyrrhonism and his opposition to what he called the ‘Dogmatists’.

Randell Mills

Randell Mills is the founder and CEO of Brilliant Light Power. He derived a grand unified theory of physics, and set about pursuing the energy applications of one of its implications: the existence of fractional energy states below the putative ground state of the bound hydrogen atom electron. I studied his book intently as a twenty-something, unlike most fringe researchers his work hangs together. He is able to talk extemporaneously about a broad set of topics and retains a vast trove of detail. Much like Stephen Wolfram’s A New Kind of Science, Mill’s GUT-CQM is heavily cross-referenced, forming an interconnected rubric. The Neuromythograph takes this one step further, by dispensing with the book altogether and focusing on modeling a dense semantic network.

Mills also described and patented an artificial intelligence scheme that coded information as “Fourier strings”–ensembles of Fourier components convoluted together to store and retrieve information. The general idea that the brain uses the Fourier transform has independently come up in neuroscience many times since. Mills’ particular scheme still influences me.

Most importantly, Mills has doggedly climbed a wall of skepticism over thirty years, and I am convinced that he will be proven right in the end. Why? Because I read his book, I read quantum theory books, I read all the criticisms of Mills’ detractors, and I see what Mills sees that very few others can see.

Jordan Peterson

The demand for and defamation campaign against Jordan Peterson made an impression upon me. There is clearly demand for spiritual information centered in something besides critical theory, but the price to be paid in the current vicious public discourse environment in the United States is high.

What made the biggest impression on me is how some neuroscientists, who ought to know better, derided Peterson’s musings about the ubiquity of male dominance levels being correlated with brain serotonin levels throughout the animal kingdom (“the lobsters”). There is massive experimental evidence for this pattern across species, including humans. But the very notion that a sex-based social hierarchy might have pre-built mechanisms in biology violates a deep-seated tenet of faith in the social constructionism pantheon. An irrational religious reaction against such blasphemy occurred. It reminds me of people who reject overwhelming evidence of human evolution from primates on the visceral basis ‘Well I didn’t evolve from no godd*mned ape’.

In neuromythography we elaborate the meaning of tonic serotonin (Nirvana) from the dorsal raphe nucleus (Aeternitas) as a ‘faith/confidence/perseverance’ amplitude signal, and phasic serotonin pulses from the median raphe nucleus (Erebus) as a ‘surprise’ signal telling us that we do not in fact have situational understanding. This provides an intuitive picture tying a hierarchy of male unflappability to serotonin levels.

An interesting footnote: Peterson’s magnum opus, Maps of Meaning, featured the Tiamat archetype. We situate this Tiamat chaos-and-confusion archetype in the midcingulate cortex, area p32pr, a brain area consistently activated in cognitive dissonance.

I think that Jordan Peterson fans and non-fans alike will find another level of depth in neuromythography.

Jiddu Krishnamurti

Jiddu Krishnamurti was identified from an early age to be a special mystic, and was groomed out of India by the esoteric Theosophy group to become World Teacher. Krishnamurti had other ideas, and became a sort of independent spiritual guru (though he would reject the term).

Krishnamurti suffered from epilepsy, and I believe specifically left temporal lobe epilepsy. I believe that this explains his slow, deliberate speaking delivery, and also how each of his words has a carefully-considered meaning behind them.

Krishnamurti often railed against “thought”, which sounds odd. If you listen more, it becomes clear that he is practicing an extreme form of mindfulness that includes not only identification of emotions, but also words and constructs and contexts and everything associated with the maelstrom of thought. When you can silence this, then truth emerges. I cannot explain this to you, you simply have to experience a quiet mind to understand.

Krishnamurti said that he sought to help people discover freedom, in themselves. I think this is a worthy goal, and I adopt it as one of my own.

Bertrand Russell described Ludwig Wittgenstein as “perhaps the most perfect example I have ever known of genius as traditionally conceived; passionate, profound, intense, and dominating.”

One of the things I admire about Wittgenstein is his appetite for conflict, to the point of carrying around a poker and waving it around. We now know that adding a bit of stress perks up noradrenaline signaling from the locus coeruleus, which in turn makes people more open to alternative ways of thinking. Wittgenstein couldn’t have known this, yet carried around a poker in order to activate philosopher locus coerulei.

Another amusing fact is that Wittgenstein dropped out of the sky with his book Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, which caused philosophy fanboys throughout Europe to swoon, as it was a progressive chain of pithy logic statements, along the lines of Euclid’s Elements. This is known as ‘early Wittgenstein’. In his middle age, Wittgenstein had the conviction that most problems in philosophy are simply semantic ‘language-games’, and therefore are not really problems at all. He advocated a more sublime view of truth, to include aesthetics, humor, and experience. This is known as ‘late Wittgenstein’, and I feel more aligned to this figure.

Wittgenstein had a familial inheritance of depression and schizophrenia. Two of his brothers committed suicide. He is an example of the connection between genius and schizophrenia.

Don’t, for heaven’s sake, be afraid of talking nonsense! But you must pay attention to your nonsense.

I am troubled that I do not have any women in this list. I certainly have many women influences, past and present. But women tend to be more balanced, circumspect, and less likely to go to war over an abstract intellectual cause. This means that there are fewer public women that you can hold them out as a canonical representative of a particular school of thought, other than generically, feminism. Perhaps this is another face of the greater male variability hypothesis, or perhaps I am under the influence of some demon whose name ends in -ism.

My neuroscience and mythography education is self-taught, and therefore I mispronounce big words in unfamiliar and proprietary ways, and have indulged in some neologisms whose meanings I try to make clear to the reader via Neuromythopedia. I make lengthy intuitive leaps and lateral connections across disciplines that can be hard to follow (we have Neuromythopedia to help with this). I have a preference for brevity and aphorisms, which can come across as arrogance, and exposition does not flow for me easily like water like it does for more productive writers. There are holes in my neuroscience knowledge, because I skipped vast areas that I was not interested in, or am not ready for yet.

My work is not intended to be good scholarship, it is at once art, allegory, and information engineering. I am mindful of the John Baez Crackpot Index, but my spirit identifies with John Conway.